In our modern world, we tend to consider mustard for its culinary importance – in sauces and in cooking as well as the ubiquitous condiment on prepared foods – but for centuries people around the globe have cultivated varieties of the plant for use in herbal remedies and for the maintenance of good health. Sanskrit and Sumerian texts from 3000 BCE record the use of mustard as a spice and in cultural rituals. Grown in the temperate regions of the world, it is considered one of the earliest of domesticated plants. As examples of its non-gustatory applications, Hippocrates used mustard packs to treat lung illnesses and to relieve congestion. In Nepal, generations of infants have been massaged with mustard oil to protect their skin and stimulate warmth. Healers in ancient Egypt used it as a medicine, as did practitioners from China to North Africa, and the Romans regarded mustard as both condiment and healing ointment. Other cultures used mustard to ease arthritis or to treat cardiovascular illnesses and over the past four millennia, herbalists and doctors have strongly recognized its importance in medicine.

Mustard belongs to the Brassicaceae family, some other members of which are broccoli, kale, cabbage, and cauliflower. As an agricultural product, the mustard plant grows from 1’ to 3’ high, has distinctive yellow flowers and oblong seedpods. While the young and tender leaves of the mustard plant are edible and are favored as greens, the mustard seed is used both as a seed itself and for the oil produced from it, yielding a pungent product not only for consumption (which also has health benefits) but for external application as well. There are three primary commercial mustards: Brassica juncea or brown mustard seed, Brassica nigra, the black mustard seed, and Sinapis alba, or white mustard. Wild mustards include treacle mustard and garlic mustard, both of which are not cultivated and are now considered invasive plants. Black mustard can be invasive as well, and can grow from 6’ to 20’ high.

Why should we care about any spice or herb, or for that matter, any plant that people bring into their daily lives? They enliven our existence by the flavor they bring to food or the easement of physical distress. Scientific exploration of the mustard plant’s qualities is tied to medical treatment, and culinary exploration of mustard creates taste sensations and the enjoyment of eating. Throughout history these paths of exploration have intertwined in noteworthy ways.

Recent discoveries suggest that use of mustard dates back more than 5,000 years. In 2013, a Neolithic pot dated as 6,100 years old was found to contain the remains of meat fats and garlic mustard seeds. This ancient pot suggests a common household usage by everyday people. The presumption is that the mixture is an example of culinary mustard use. But could it not be both food and medicine? Could it not be a Stone Age example of “chicken soup”?

A trove of herbalists, holistic medical practitioners, nutritionists, philosophers, and botanical illustrators have documented the ethnobotanical history and wonder of the mustard plant.

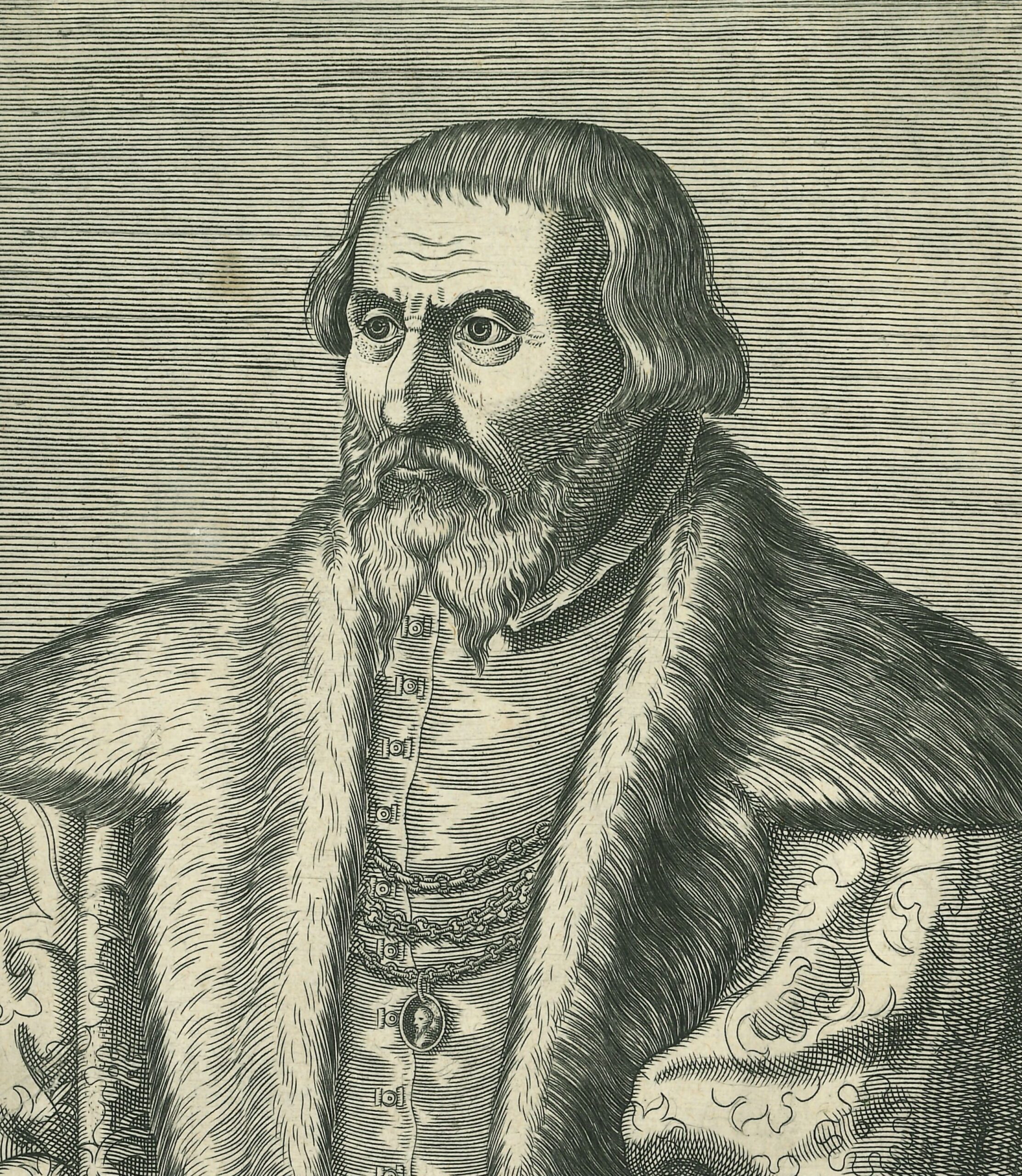

Pedanius Dioscorides (d. 90 CE), a Turkish-born Greek physician and botanist who wrote a five-volume treatise on medicine, was one of the earliest to promote the use of mustard as a medical treatment. His treatise was a standard reference work for over 1,500 years and because of its great influence in the training of physicians, mustard achieved a standard presence in the healer’s kit bag of cures.

Dioscorides believed in the use of mustard in plasters and poultices as an important part of treatment not only for aches and congestions, but also for easing the pain and discomfort of pregnancy and childbirth. The heat generated by the poultice created a soothing warmth and relaxation of muscles – but only if wasn’t left on the body for too long! Because of that heat, mustard could also cause skin burns if not carefully attended. Mustard also reduced the pain of headaches and in tumors of the tonsils (essentially tonsillitis).

Title page of Pharmacorum Simplicum Reique Medicae Libri VII, (1529) by Pedanius Dioscorides. Portrait of Dioscorides from Kevin Grace Collection.

One of the most famous health practitioners of his time, Nicholas Culpeper, was a 17th century English botanist, herbalist, physician, and astrologer who strived to consider all possibilities in exploring health and healing. In his comprehensive herbal, he described the botany and physical description of the mustard plant in this way:

…the flowers are small and yellow of four leaves a piece, set many together and flowering by degrees; before they have done flowering, the spike of he seed-vessel is extended to a great length…full of round, dark, brown seed of a hot biting taste.

As a botanist Culpeper described mustard as to how it was found in the wild and in its agricultural state so other practitioners would have a clear and common-sense guide to recognizing the plant and harvesting it. His note about the “hot biting taste” of the seed was directed more to the expectation one should have when taking it internally for medicine rather than its use in cooking.

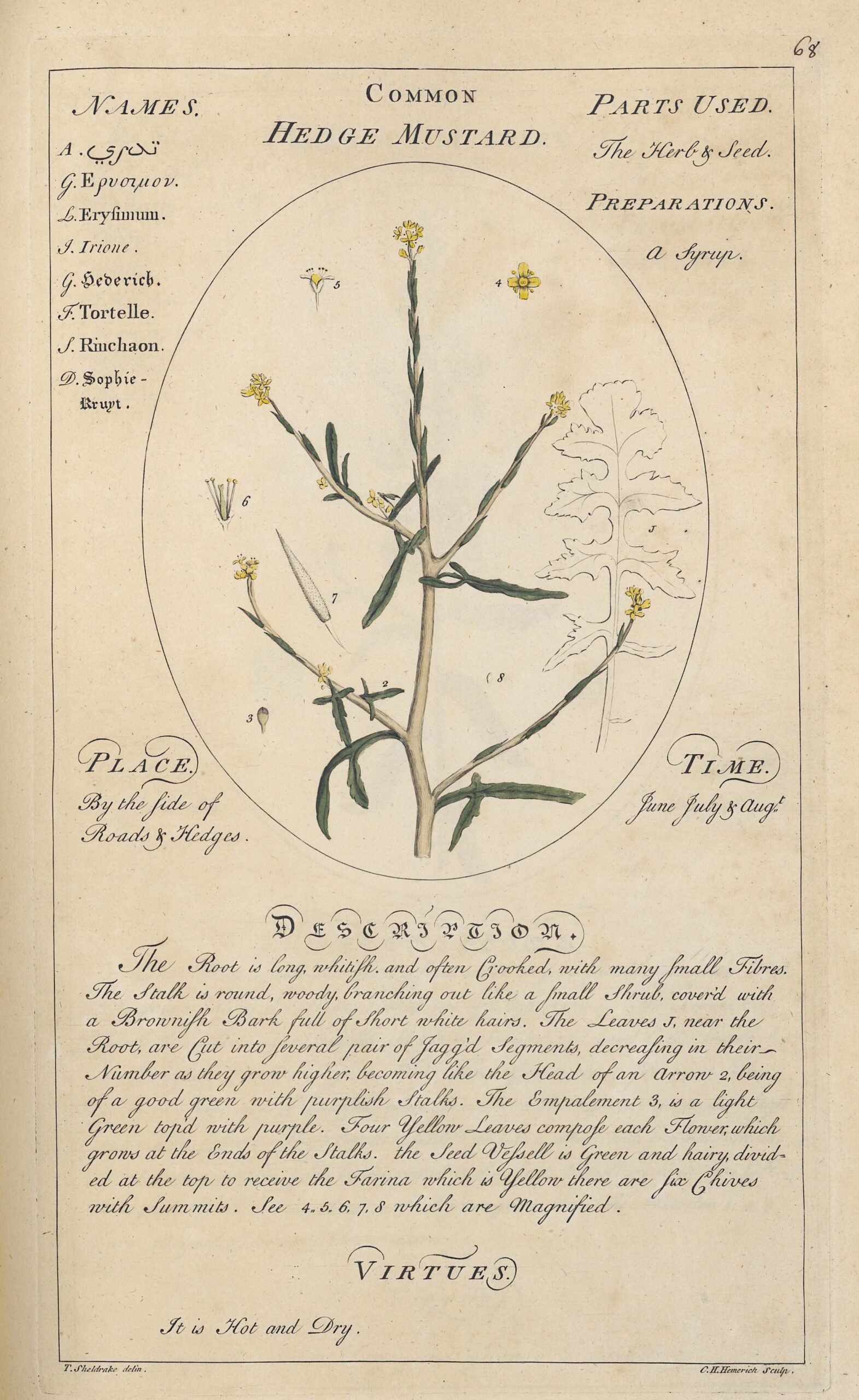

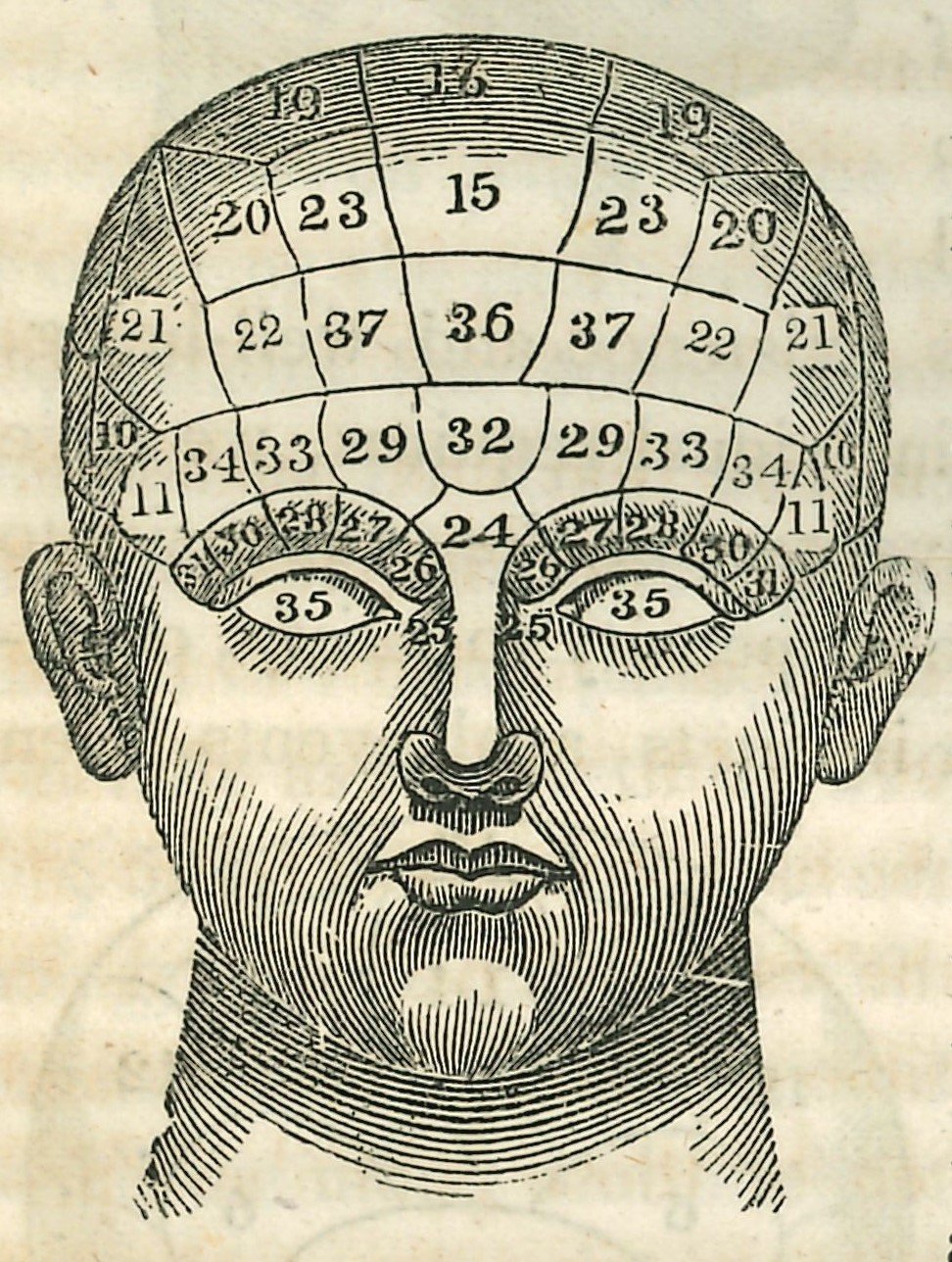

Culpeper’s influential book, The Compleat Herbal, was first published in 1653 and remained a standard medical and herbal guide for two centuries. This is his sketch of the mustard plant, and he listed its “virtues”:

Culpeper’s influential book, The Compleat Herbal, was first published in 1653 and remained a standard medical and herbal guide for two centuries. This is his sketch of the mustard plant, and he listed its “virtues”:

It strengthens the stomach; helps digestion; and useful in apoplexies, lethargy, and palsy, especially of the tongue. When it is infused in wine or ale, it is effective against scurvy or dropsy, and, it aids urination and stimulates menses.

Culpeper's illustration of treacle mustard is a plant rarely used in cuisine. The seeds were regularly used in medicinal plasters. He noted that it grows in cornfields and flowers in May, and it acts as a diuretic and helps relieve gout.

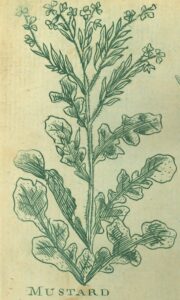

Culpeper never paired turmeric with mustard, as had been the case for millennia in South Asian cuisine, but did recognize its health properties, "…opens obstruction of the viscera, helps the jaundice, provokes urine…"

Turmeric with its saffron-yellow interior, is an ingredient in American mustard that gives it the bright yellow color.

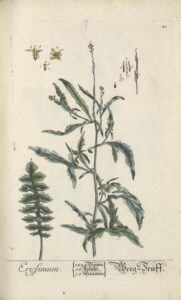

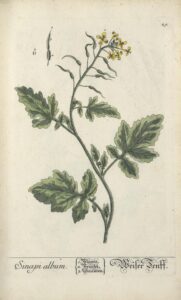

Illustrations from Culpeper's The Compleat Herbal, or, Family Physician from 1787.

Culpeper’s work, which was written in English, represents expanded access to information about mustard. Dioscorides spoke to the elite, who read Greek and practiced medicine. Culpeper’s common language was geared to everyday people. But for thousands of years, ordinary people relied on their own experiences and the handing down of tradition.

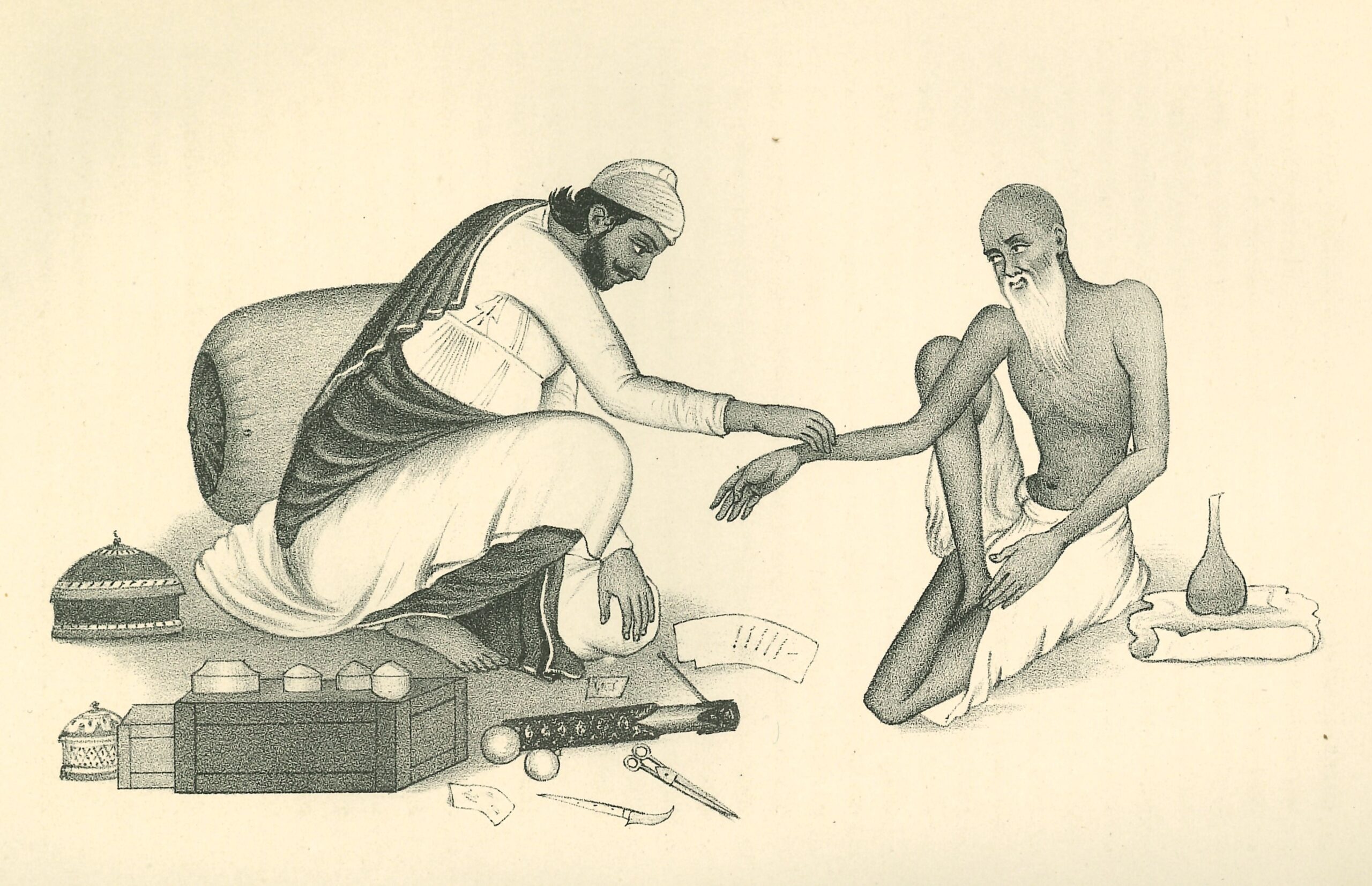

During the Age of Enlightenment and continuing into the 19th century, global exploration contributed to knowledge about the customs and cultural diversity of the world. One of the results of European colonization and exploitation of Asian and African cultures in the 18th and 19th centuries was detailed ethnographic reports and travel accounts documenting the lifeways of indigenous people. In South Asia, military officials, physicians, scientists, and journalists frequently commented on the everyday life that included the uses of herbal cures and native cuisine. John Martin Honigberger (1795-1869), for example, was an Austrian physician who traveled widely in India, the Punjab, and Afghanistan, collecting plants and writing about their use in traditional medicine, including the mustard plant in the north of India.

Illustration from Thirty-five Years in the East (1852) by John Martin Honigbereger. View book digitally.

As the age of the Enlightenment gained a foothold in Europe, there was a concerted effort to examine the world in a more holistic way that married disciplines so they could complement each other. This included an expansion of the scientific view of the world of flora with more accurate illustration of plants, as reflected in the work of the 18th century botanist and physician, Thomas Sheldrake, whose work flourished in the 1750s. Sheldrake’s illustrations were more artful and detailed, rendering a scientific work with aesthetically accurate drawings. The first edition of his monumental folio work on plants, Botanicum Medicinale, is dated around 1768 and may have been published posthumously.

Sheldrake’s botanical artwork was noted for its beauty and clear delineation of a plant’s composition. Two mustard plants he documented, hedge mustard and treacle mustard, were typical of his style: elegant hand-colored drawings in an oval framework with the plant’s name above and its “virtues”, or uses, below. The extraordinary grace not only of his art but of the typography accompanying it make Sheldrake’s work one of the most beautiful books of the age.

Illustrations from Botanicum Medicinal by Thomas Sheldrake (1768). View this book digitally.

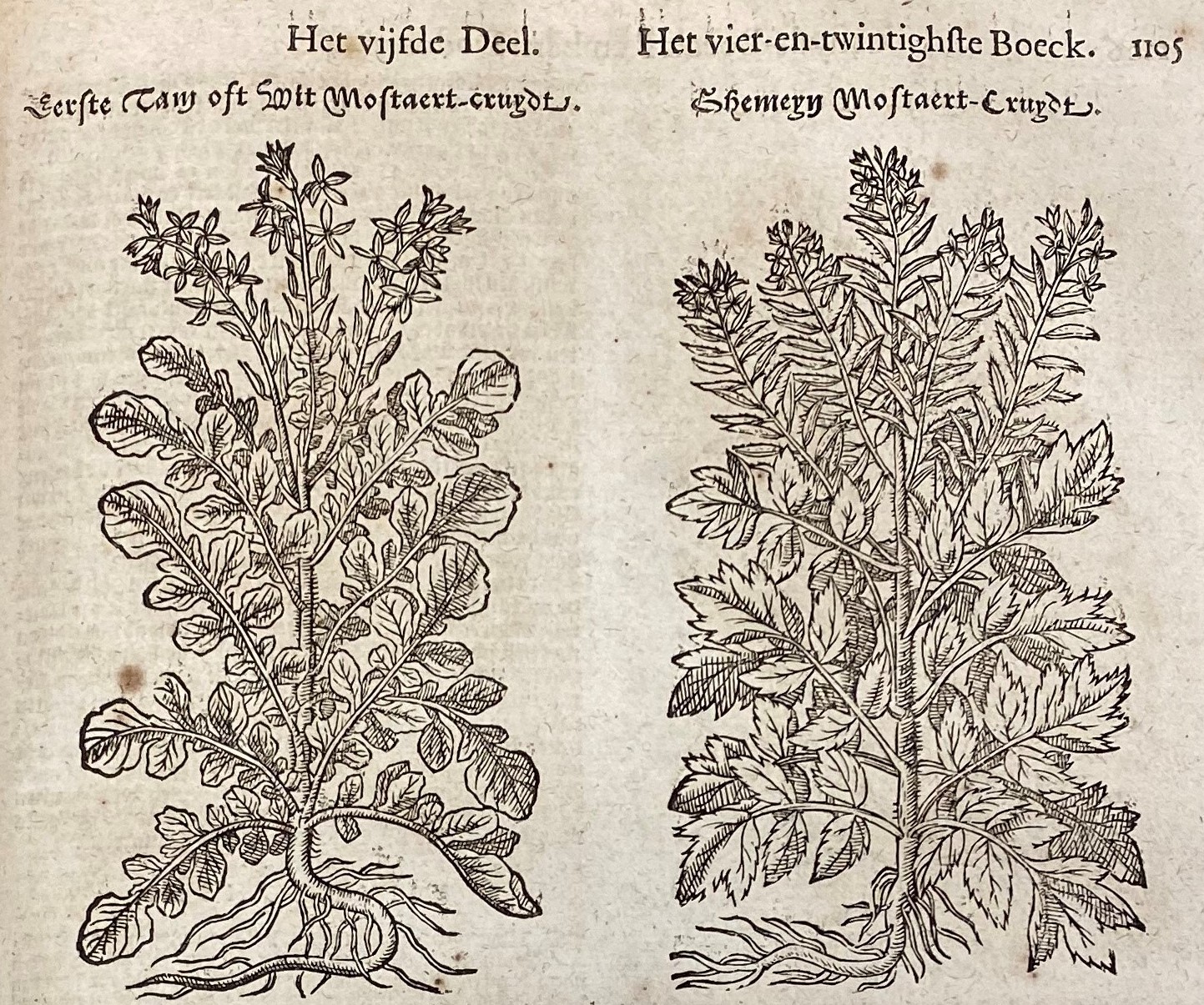

Sheldrake, Culpeper, and their contemporaries’ work rested upon the accomplishments of scientists from the previous two centuries. One such luminary was the 16th century Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens, who attributed to mustard an extensive list of benefits. He stated that it treated dropsy, sciatica, deafness, poor eyesight, agues, and phlegm, and that it aided urination and would rid a person of freckles and spots. It would be interesting to know how some of these scientific uses were evident in daily life – elimination of freckles and spots? Improvement of deafness and eyesight? Close observation, or anecdotal accounts? As each scientific age came about, cause and effect of mustard treatment would vary with some effects disproved and other sometimes bizarre benefits of mustard promoted.

But then, Dodoens also said of mustard that “The perfume or savour there of driveth away all venomes and venomous beasts.”

Pietro Mattioli (1501-1577) was an influential Italian physician and botanist (the first to identify the medical condition of being allergic to cats!) who often used prisoners in his experiments with poisonous plants. And he had a tendency to viciously attack other scientists who disagreed with him. But…he also loved mustard.

Mattioli studied mustard plants, sketching the varieties he found, and he promoted the health benefits of eating mustard: “It prevents us from giving up.” For all his contrariness and his questionable experimental methods, Mattioli built upon what had been learned by scientists before him. The work of people like Mattioli and Dodoens was the foundation of science – each succeeding generation could embrace the real and reject the imagined. They were not always successful or rational in doing so, but one thing continued to build upon another, in both the study of mustard and of medicine.

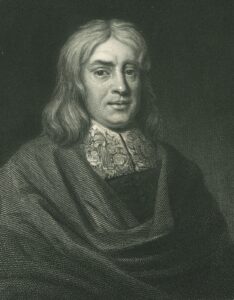

In the 17th century, English physician Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) compiled a medical book that stayed in active consultation among health practitioners for nearly 200 years. He was another scientist in the tradition of Dioscorides, Dodoens, and Mattioli. His treatise relied heavily on native plants and their medicinal use. Of mustard he said: “But for the advantage of beginners, I will set down the Remedy I am wont to use.” That is, mustard was good for treating gout, heart failure, cramps, worms, rashes, and spasmodic coughs. As to worms, there is doubt of course, unless the heat of mustard drove them out of the body! For the rest, well yes, Sydenham was close to the mark.

In the 17th century, English physician Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) compiled a medical book that stayed in active consultation among health practitioners for nearly 200 years. He was another scientist in the tradition of Dioscorides, Dodoens, and Mattioli. His treatise relied heavily on native plants and their medicinal use. Of mustard he said: “But for the advantage of beginners, I will set down the Remedy I am wont to use.” That is, mustard was good for treating gout, heart failure, cramps, worms, rashes, and spasmodic coughs. As to worms, there is doubt of course, unless the heat of mustard drove them out of the body! For the rest, well yes, Sydenham was close to the mark.

Portrait of Sydenham from Kevin Grace Collection.

During the Enlightenment, there was considerable concern about the advancement of science and its conflict with traditional religious belief. Some scientists arduously attempted to accommodate both and provide rational explanations of phenomena that would support the tenets of faith.

Swiss botanist, physician, mathematician, and astronomer Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672-1733) was one of these scientists of his time who attempted to reconcile scientific fact and religious belief. Scheuchzer traveled widely in Europe collecting fossils and plants in order to come to a reasonable understanding of them. Of course, in his native Switzerland he also gathered accounts of dragons and illustrated them for museum purposes. But it is his Physica Sacra, published in four volumes from 1731-1735, in which he developed his view of “natural theology”, using the Bible to describe the natural world. In these richly illustrated books, one view is of a massive mustard tree, symbolizing the various Gospel verses of Mark, Matthew, and Luke which speak of faith as a tiny mustard seed that can grow to a great height. Not confined to the Christian Bible, a parable of the mustard seed was also an element of the Talmud and the Qur’an.

During this period, artists furthered scientific learning through their botanical illustrations which combined art with more accurate depictions of plants. Elizabeth Blackwell (1707-1758) was preeminent in the field and was one of the earliest women to make a living from her work. Her career would lead the way in the next century for more women in scientific illustration. Blackwell was a Scots-born botanical illustrator whose beautiful work. A Curious Herbal, was published in two volumes from 1737-1739. Designed to be used as a reference work for apothecaries and physicians in concocting their medicines, her book contained mustard art as part of a standard herbal. In her work, she illustrated hedge mustard, white mustard, and treacle mustard, noting that the latter grew in England’s Essex region, usually in cornfields and flowering in May.

Blackwell compiled her botanical illustrations in part to support her husband, Alexander Blackwell, a failed physician and printer who found himself in debtors’ prison. He eventually became a farm manager and then landed in Sweden in 1747 where he ran afoul of the Crown Prince. Accused of an attempted assassination of the prince, Blackwell was sentenced to the execution block. He took a philosophical view, and as he was led to his demise by the executioner, he remarked that it was his first beheading and he would need assistance in properly placing his head. The axe fell on August 9, 1747.

Illustrations of mustard from Blackwell's Herbarium Blackwellianum. View entire work digitally.

By the 19th century, herbalists and medical practitioners had a better understanding of the beneficial use of mustard. As an example, in Samuel Thomson’s 1835 remedy book, he stated that mustard:

is good to create an appetite and assist the digesture; and given in hot water, sweetened, will remove pain in the bowels and stomach. It is frequently used for rheumatism, both internally and externally.

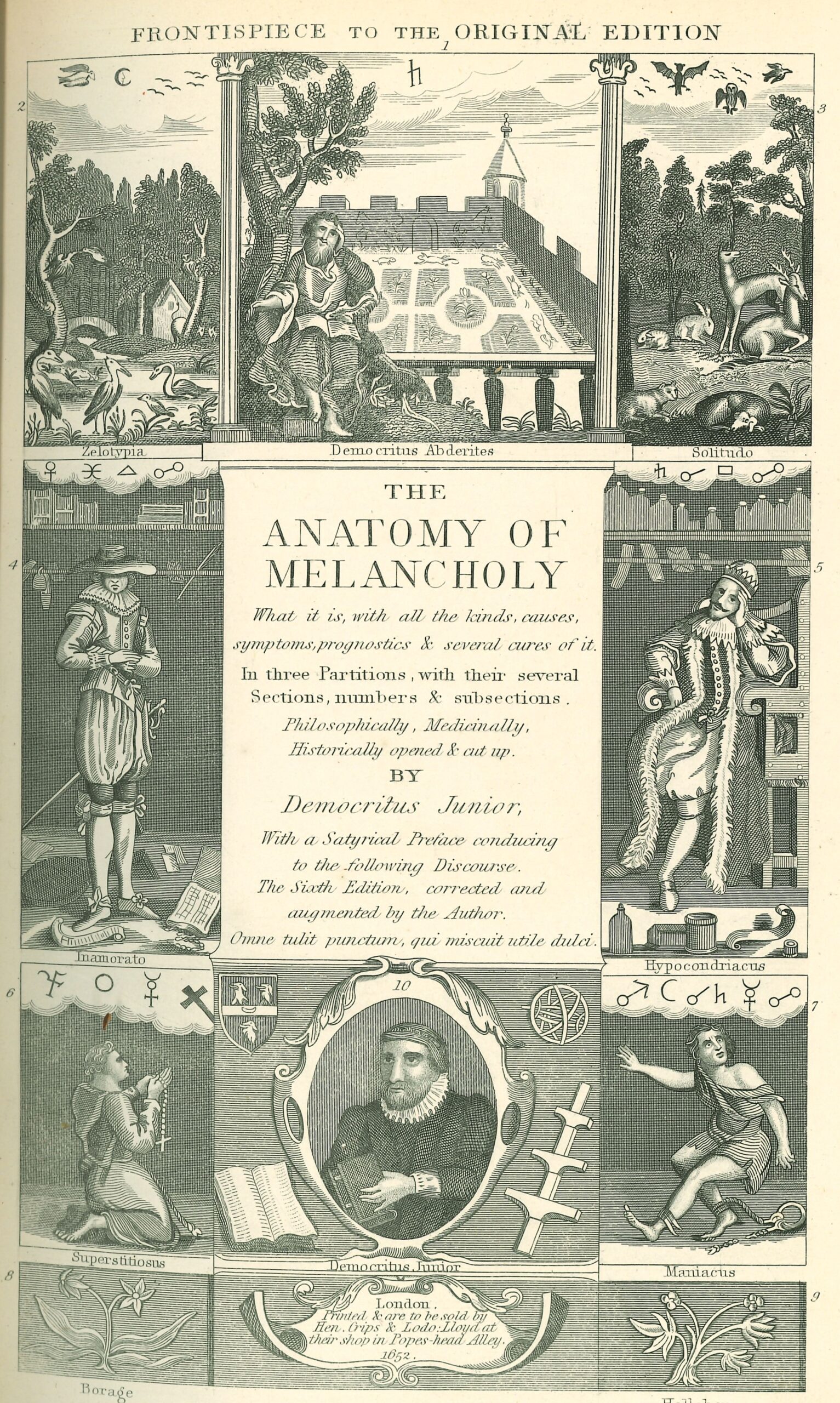

But an opposing view - and an example that scientific belief does not progress in a logical manner - was that of Robert Burton, who believed the consumption of spices provokes “head melancholy.” Mustard was among the spices he listed in his book, as it had a “corrosive effect” on the mind and body. It provides “gross fumes to the brain and make men mad.”

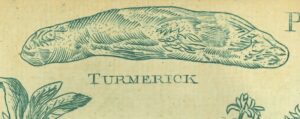

Not far off the path from Robert Burton were two of the strongest 19th century promoters of vegetarian diets and clean living, Sylvester Graham (of the graham cracker) and John Kellogg (of the corn flake). Both men believed food should be completely bland. They stormed against the use of mustard (and other spices) because it inflamed the passions, leading to the dangers of sexual excess. Graham also was a believer in phrenology, but he didn’t identify the exact skull bump that identified the depravity of the mustard-eater.

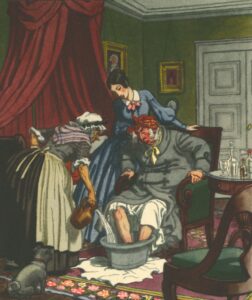

The various uses of mustard as medicine were fairly well established by the late 1800s. Mustard plasters in the home were common standbys for domestic health care, and pharmacies included them in standard inventory, either as ready-to-apply plasters or as plasters to be moistened at home and applied to chests, backs, legs, bellies, and heads to relieve pain and congestion. And of course, there was still the danger of leaving the plasters on too long and risking serious burns. In addition to the plaster, there was also the use of mustard in footbaths. This mid-20th century lithograph by French commercial artist Leon Ullmann was created for the pharmaceutical industry, showing the use of a mustard footbath at home. Mustard was a common element of this home treatment for hundreds of years, but fell out of favor in the last few generations as mentholated rubs became widely used and without the risk of burns. However, studies in the past two decades on the health effectiveness of mustard and its place in traditional medicine have created renewed interest in its place in the home.

Today the health benefits and medicinal use of mustard continue to be explored as they have for thousands of years. As one example, for centuries mustard has been part of Ayurvedic medicine in India, combining medicine, religion, and philosophy, and again of course, the religious parable of the mustard seed can be found in the theological writings of the Christian, Buddhist, and Islamic faiths. Consider this of the tiny mustard seed: only 6 to 10 pounds of seed is used to plant an acre of mustard. An increase – or revival – of medical use has led to increased scientific research of the mustard plant, and particularly mustard oil. Mustard is cholesterol-free and contains calcium, iron, phosphorus, protein, zinc, manganese, and omega-3 fatty acids. Much of this research is being done in South Asia, and rigorous studies need to be done throughout the world, but some of the wide-ranging results indicate that mustard oil has a positive effect on liver function and metabolic rates, helps reduce blood pressure and hypertension, and is antibacterial and antimicrobial. As an anti-inflammatory it relieves joint pain. Other research indicates mustard could prove to be an effective element in treating colon and colorectal cancers.

Agriculturally, most of the world’s mustard in our time is produced in Canada, with Nepal growing the second greatest amount. Other significant mustard-producing countries are Russia, India, Myanmar, the United States, Ukraine, and Germany. Mustard is sown in late fall and early winter, with the harvest in late spring and early summer. And as it grows, the yellow-flowering mustard is one of the most beautiful of cultivated plants.

There is a specific confluence of beauty found in science and art and literature that reflect our daily experiences. So is the case with the simple mustard plant. In her 1949 book, I Leap Over the Wall, British author and former nun Monica Baldwin recounted the time when she left an English convent after twenty-eight years of seclusion and was traveling through the countryside by train:

I suppose I had been shut away for so long that I had forgotten what mustard fields looked like; but they seemed to me one of the loveliest things I had seen since I came out. Sheet upon sheet of blazing yellow, half-way between sulphur and celandine, with hot golden sunshine pouring down upon them out of a dazzling June sky. It thrilled me like music.

This digital exhibit was written by and based on the research of 2022 Curtis Gates Lloyd Fellow, Kevin Grace. Grace is the recently retired Head of the Archives & Rare Books Library at the University of Cincinnati. He also taught in the University Honors Program with experiential learning for his students provided by study tours around the world. Grace holds degrees in Anthropology from Wright State University and the University of Cincinnati with a focus on folk cultures. His expertise in rare books and manuscripts ranges from literary ethnographic travel and scientific accounts from the 15th to the early 20th centuries, to the cross-cultural customs of everyday life.